The secretory activity of the pineal gland is only partially understood. Its location deep in the brain suggested to philosophers throughout history that it possesses particular importance. This combination led to its being regarded as a “mystery” gland with mystical, metaphysical, and occult theories surrounding its perceived functions.

In the late 19th century Madame Blavatsky (who founded theosophy) identified the pineal gland with the Hindu concept of the third eye or the Ajna chakra. This association is still popular today.

The pineal gland was originally believed to be a part of a larger organ. In 1917 as one of the first experiments conducted to elucidate the function of the pineal, extracts of pineal glands from cattle were added to water containing tadpoles. Interestingly, the tadpoles responded by becoming very light in color or almost transparent due to alterations in melanin pigment distribution. Dermatology professor Aaron B. Lerner and colleagues at Yale University, hoping that a substance from the pineal might be useful in treating skin diseases, isolated and named the hormone melatonin in 1958. The substance did not prove to be helpful as intended, but its discovery helped solve several mysteries around this gland.

Rick Strassman, an author and Clinical Associate Professor of Psychiatry at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, has theorized that the human pineal gland is capable of producing the hallucinogen N, N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT) under certain circumstances. In 2013 he and other researchers first reported DMT in the pineal gland of rodents.

Melatonin

The pineal gland or epiphysis synthesizes and secretes melatonin, a structurally simple hormone that communicates information about environmental lighting to various parts of the body. Ultimately, melatonin has the ability to entrain biological rhythms and has important effects on reproductive function of many animals.

Anatomy of the Pineal Gland

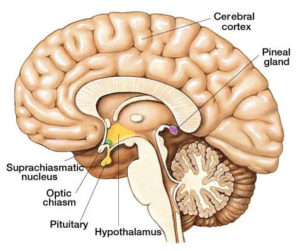

The pineal gland is a small organ shaped like a pine cone (hence its name). It is located on the midline, attached to the posterior end of the roof of the third ventricle in the brain. The pineal varies in size among species; in humans, it is roughly 1 cm in length, whereas in dogs it is only about 1 mm long. To observe the pineal, reflect the cerebral hemispheres laterally and look for a small grayish bump in front of the cerebellum.

Histologically, the pineal is composed of “pinealocytes” and glial cells. In older animals, the pineal often contains calcium deposits (“brain sand”).

How does the retina transmit information about light-dark exposure to the pineal gland?

Light exposure to the retina is first relayed to the suprachiasmatic nucleus of the hypothalamus, an area of the brain well known to coordinate biological clock signals. Fibers from the hypothalamus descend to the spinal cord and ultimately project to the superior cervical ganglia, from which postganglionic neurons ascend back to the pineal gland. Thus, the pineal is similar to the adrenal medulla in the sense that it transduces signals from the sympathetic nervous system into a hormonal signal.

Melatonin: Synthesis, Secretion, and Receptors

The precursor to melatonin is serotonin, a neurotransmitter that itself is derived from the amino acid tryptophan. Within the pineal gland, serotonin changes into melatonin.

Synthesis and secretion of melatonin is dramatically affected by light exposure to the eyes.

Biological Effects of Melatonin

Melatonin has important effects in integrating photoperiod and affecting circadian rhythms. Consequently, it has been reported to have significant effects on reproduction, sleep-wake cycles and other phenomena showing circadian rhythm.

Effects on Sleep and Activity

Light is one of the major regulators of normal sleep patterns. One topic that has garnered a large amount of interest is using light therapy to induce the secretion of melatonin, to treat sleep disorders. There is some indication that melatonin levels are lower in elderly insomniacs relative to age-matched non-insomniacs, and light therapy in such cases appears to be very beneficial in correcting the problem.

Another sleep disorder is seen in shift workers, who often find it difficult to adjust to working at night and sleeping during the day. The utility of light therapy to alleviate this problem is shown to be very effective. Still, another condition involving disruption of circadian rhythms is jet lag. In this case, it has repeatedly been demonstrated that receiving light at the appropriate time of day will shift the body clock in the correct direction and reduce the number of days that the symptoms of jet lag are experienced.

In addition to being able to alter the timing of the body clock, light also has a number of other acute (instant, short-term) effects on our physiology and behavior. Bright light can rapidly enhance our level of alertness, our ability to perform certain tasks and also our mood.

DMT

Dimethyltryptamine or DMT, often referred to as the “spirit molecule,” is one of the most intriguing psychedelic substances on Earth — not just because of the wild experiences reported by DMT users, but because there has been some research that suggests it is produced in our own bodies.

Terence McKenna, an ethnobotanist, and psychonaut who experimented with the drug 30 to 40 times throughout his career said in his book The Archaic Revival, “It was really the DMT that empowered my commitment to the psychedelic experience. DMT was so much more powerful, so much more alien, raising all kinds of issues about what is the reality, what is language, what is the self, what is three-dimensional space and time, all the questions I became involved with over the next twenty years or so.”

McKenna, along with many others who have tried the drug, insists that the experience is so surreal that it cannot be accurately translated into words — “In other words, what DMT does can’t be downloaded into as low-dimensional a language as English,” describes McKenna.

In 2013, researchers reported finding DMT in the pineal gland of rodents — the pineal gland in the brain produces melatonin (a hormone derived from serotonin) which affects sleep patterns and circadian rhythms. This study sparked the widespread assertion that DMT occurs in the human pineal gland and is released during dreams as well as at or shortly before birth and death, but the claim still needs to be scientifically verified with further research.

Dr. Rick Strassman, a Stanford University graduate with a specialization in psychiatry and psychopharmacology, is the torch bearer behind the idea that DMT is released in the pineal gland. He took on a five-year project to investigate the effects of DMT and administered about 400 doses of the drug to nearly five dozen heavily pre-screened volunteers. Throughout his work, he and his team coined a new rating scale called the Hallucinogen Rating Scale (HRS), which has been widely accepted throughout the international research community — over 45 articles have documented its use as a solid instrument for measuring psychological effects.

Interestingly, based on his extensive research and observations, Dr. Strassman hypothesizes that when a person is approaching death or possibly even just in a dream state, the body releases relatively large amounts of DMT. The majority of his volunteers reported profound encounters with nonhumans and deep spiritual experiences, and Dr. Strassman believes that DMT could explain some of the wild imagery described by survivors of near-death experiences as well as those recounting their dreams.

However, although this hypothesis has yet to be confirmed with scientific evidence, Strassman’s research did produce some striking facts about DMT.

In his book, DMT: The Spirit Molecule, he writes that DMT “exists in all of our bodies and occurs throughout the plant and animal kingdoms. It is a part of the normal makeup of humans and other mammals; marine animals; grasses and peas; toads and frogs; mushrooms and molds; and barks, flowers, and roots.”

He continues, “Twenty-five years ago, Japanese scientists discovered that the brain actively transports DMT across the blood-brain barrier into its tissues. I know of no other psychedelic drug that the brain treats with such eagerness. This is a startling fact that we should keep in mind when we recall how readily biological psychiatrists dismissed a vital role for DMT in our lives. If DMT were only an insignificant, irrelevant by-product of our metabolism, why does the brain go out of its way to draw it into its confines?”

It goes without saying that DMT strikes interest not only based on the reports of the strange, vivid hallucinations induced by the drug but to unravel the mystery of its true purpose within our brains.

Read more:

Watch:

DMT: The Spirit Molecule (2010)